Command-line utilities like lsof, ps, and netstat may be basic, but they are surprisingly powerful. Many of us still love them and use them regularly. For those that aren’t familiar: * ps: displays the currently-running processes * netstat: displays network connections, routing tables, and other network statistics * lsof: lists open file descriptors and the processes that opened them

Wouldn’t it be cool if these tools had Wireshark-like filtering capabilities and the ability to run on any given point in time, past or present – for example when an error happens or when a process exits? In this post I’d like to show you how to accomplish exactly that – using sysdig of course! I’m dividing up the post into two parts:

A bit of easy theory to explain how lsof works (and other tools like ps and netstat), and how sysdig compares to them.

A set of practical use cases that will teach you how to leverage filters and sysdig’s back in time functionality to troubleshoot issues or detect leaks like a pro.

If you are not interested in theory, feel free to skip the first part and jump to the section named “lsof + filters”.

lsof and the /proc file system

lsof does something that in principle is quite simple: it lists the open file descriptors for a machine or for a process.

$ sudo lsof -p 41113 COMMAND PID USER FD TYPE DEVICE SIZE/OFF NODE NAME mysqld 41113 mysql cwd DIR 253,1 4096 931157 /opt/lampp/var/mysql mysqld 41113 mysql rtd DIR 253,1 4096 2 / mysqld 41113 mysql txt REG 253,1 10091608 945718 /opt/lampp/sbin/mysqld mysqld 41113 mysql mem REG 253,1 162616 695538 /usr/lib64/ld-2.16.so mysqld 41113 mysql mem REG 253,1 2071376 695539 /usr/lib64/libc-2.16.so mysqld 41113 mysql mem REG 253,1 22440 695549 /usr/lib64/libdl-2.16.so mysqld 41113 mysql mem REG 253,1 144552 681357 /usr/lib64/libpthread-2.16.so mysqld 41113 mysql mem REG 253,1 47624 695557 /usr/lib64/librt-2.16.so mysqld 41113 mysql mem REG 253,1 1139968 695540 /usr/lib64/libm-2.16.so mysqld 41113 mysql mem REG 253,1 434224 682502 /usr/lib64/libfreebl3.so mysqld 41113 mysql mem REG 253,1 43808 695611 /usr/lib64/libcrypt-2.16.so mysqld 41113 mysql mem REG 253,1 91352 704978 /usr/lib64/libgcc_s-4.7.2-20121109.so.1 mysqld 41113 mysql mem REG 253,1 62416 670511 /usr/lib64/libnss_files-2.16.so mysqld 41113 mysql mem REG 253,1 973680 946274 /opt/lampp/lib/libstdc++.so.6.0.8 mysqld 41113 mysql mem REG 253,1 1851440 946268 /opt/lampp/lib/libcrypto.so.1.0.0 mysqld 41113 mysql mem REG 253,1 90128 946242 /opt/lampp/lib/libz.so.1.2.8 mysqld 41113 mysql mem REG 253,1 416080 946237 /opt/lampp/lib/libssl.so.1.0.0 mysqld 41113 mysql 0r CHR 1,3 0t0 1028 /dev/null mysqld 41113 mysql 1w REG 253,1 40605 948996 /opt/lampp/var/mysql/localhost.localdomain.err mysqld 41113 mysql 2w REG 253,1 40605 948996 /opt/lampp/var/mysql/localhost.localdomain.err mysqld 41113 mysql 3uW REG 253,1 329252864 948997 /opt/lampp/var/mysql/ibdata1 mysqld 41113 mysql 4u REG 0,31 0 15836611 /tmp/ibBexiL2 (deleted) mysqld 41113 mysql 5u REG 0,31 0 15836612 /tmp/ib85pBUO (deleted) mysqld 41113 mysql 6u REG 0,31 0 15836613 /tmp/ibrfMY3A (deleted) mysqld 41113 mysql 7u REG 0,31 0 15836614 /tmp/ibh6XUfn (deleted) mysqld 41113 mysql 8uW REG 253,1 5242880 948998 /opt/lampp/var/mysql/ib_logfile0 mysqld 41113 mysql 9uW REG 253,1 5242880 948999 /opt/lampp/var/mysql/ib_logfile1 mysqld 41113 mysql 10u IPv4 15836616 0t0 TCP *:mysql (LISTEN) mysqld 41113 mysql 11u REG 0,31 0 15836615 /tmp/ibY8sHya (deleted) mysqld 41113 mysql 12u unix 0xffff88000cac8680 0t0 15836617 /opt/lampp/var/mysql/mysql.sock ...

Despite being based on a simple concept, lsof is super useful in a bunch of situations. The reason is that pretty much anything on a unix machine is represented as a file descriptor: files, directories, network connections, pipes, events, and much more. As a consequence, lsof can see a lot of stuff and can be used to answer many interesting questions. For example:

- Which network connections does process X have?

- Who is connecting to a specific endpoint?

- Which processes have open files in /etc?

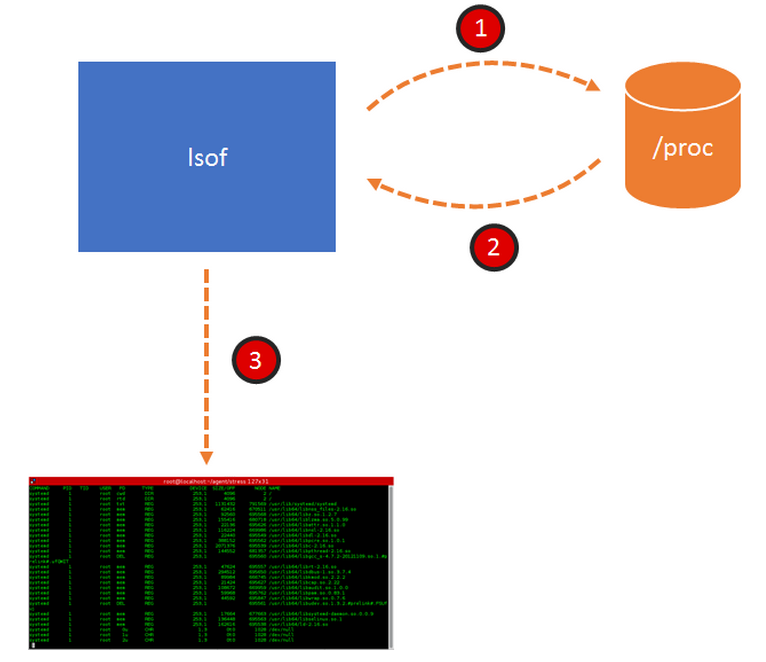

lsof leverages an extremely powerful feature of the linux kernel: the /proc file system. The kernel exports a lot of internal information under /proc, which you can browse with ls and manipulate with a normal text editor. If you look at the content of the /proc directory, you see several subdirectories with a number as their name. Those are PIDs, and each of those subdirectories contains the details of a specific process. Inside, among other things, there’s the list of file descriptors for that process. At this point, understanding what lsof does becomes pretty easy and is shown in the picture below.

- navigates /proc

- collects all the FD information it can find

- spits the information to the console.

Most of the other linux tools that you use every day (ps, top, netstat to name a few) work exactly the same way. You can think about them as user interfaces for /proc.

How is sysdig different?

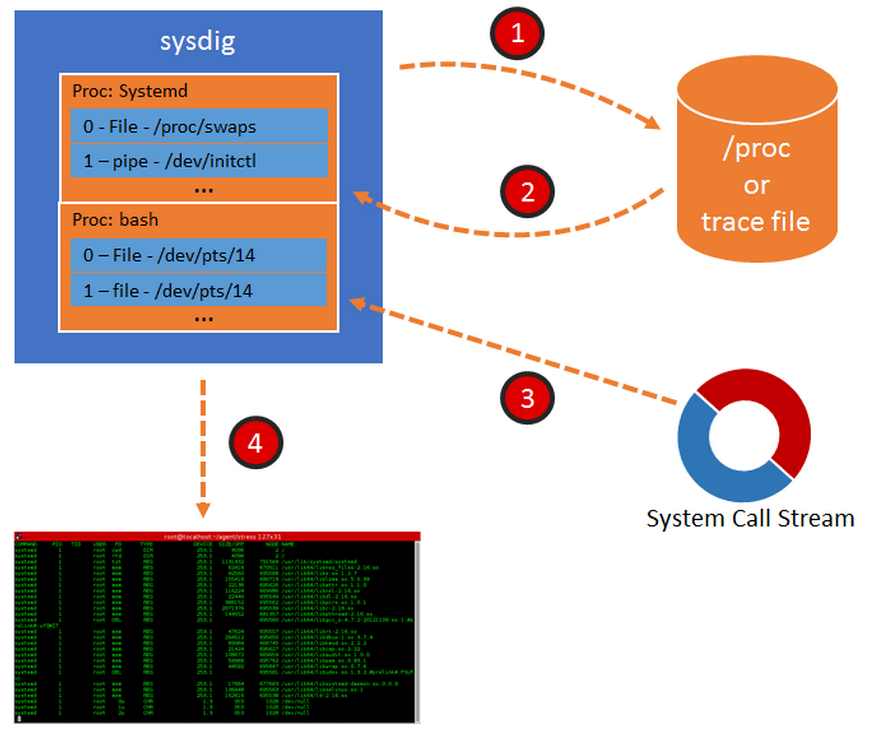

Sysdig operates in a slightly more complex way, shown in this picture:

1. Sysdig collects data from /proc when it starts, exactly like lsof or ps, but … 2. Instead of just dumping the results, it stores them in a table. This table contains the list of processes and threads and, for each of them, the list of FDs. 3. Sysdig then starts capturing every system call. When it encounters a system call that causes a change in system state, sysdig updates the table. For example, an open() or a connect() cause a new FD to be created in the system; sysdig intercepts them and adds an entry to the table. A close() causes an FD to disappear from the system, and therefore sysdig removes it from its table. All of this is super fast, and the result is that now sysdig has a mirror of /proc, constantly up to date, that can be queried with minimal overhead. 4. Thanks to this constantly updated table, sysdig can do a bunch of magic, some of which is going to be shown in the rest of this blog post.

1. Sysdig collects data from /proc when it starts, exactly like lsof or ps, but … 2. Instead of just dumping the results, it stores them in a table. This table contains the list of processes and threads and, for each of them, the list of FDs. 3. Sysdig then starts capturing every system call. When it encounters a system call that causes a change in system state, sysdig updates the table. For example, an open() or a connect() cause a new FD to be created in the system; sysdig intercepts them and adds an entry to the table. A close() causes an FD to disappear from the system, and therefore sysdig removes it from its table. All of this is super fast, and the result is that now sysdig has a mirror of /proc, constantly up to date, that can be queried with minimal overhead. 4. Thanks to this constantly updated table, sysdig can do a bunch of magic, some of which is going to be shown in the rest of this blog post.

But wait, sysdig can also take trace files! When you do that, using the sysdig -w command line flag, sysdig starts by scanning /proc and dumping the whole process table to disk, and then saves each system call to file after that. Later, when you open the file for analysis, the process is similar to the one depicted above, but this time the process table is loaded from file. This means that you can enjoy a precise snapshot of the state of the system on which the capture was taken, including its evolution in time according to the events that were captured. Think about it as a Tivo for your linux instance. All right, enough theory. Let’s see what we can do with this data!

lsof + filters

The latest sysdig release adds three new entries to the sysdig chisel library: lsof, ps, and netstat. The names should make it very clear what they do. It’s worth pointing out, however, that the data comes from the sysdig process table and not from proc and this means that I can use sysdig’s powerful filtering language to decide what to see and when I want to see it. Let’s start with the what. By default, the lsof chisel shows the full system state, exactly like the lsof tool, which is usually a lot of information. I can slice and dice it any way I want with filters. Here, for example, is the list of log files that apache is writing to:

$ sudo sysdig -c lsof "'proc.name contains http and fd.name contains log'" COMMAND PID TID USER FD TYPE NAME httpd 40720 40720 root 2 file /opt/lampp/logs/error_log httpd 40720 40720 root 8 file /opt/lampp/logs/error_log httpd 40720 40720 root 9 file /opt/lampp/logs/access_log httpd 40720 40720 root 10 file /opt/lampp/logs/access_log httpd 40720 40720 root 11 file /opt/lampp/logs/ssl_request_log

(note how the filter is in both single and double quotes. Sorry for the weird syntax…) And here’s the list of network connections established by the user root:

$ sudo sysdig -c lsof "'fd.type=ipv4 and user.name=root'" COMMAND PID TID USER FD TYPE NAME sshd 891 891 root 3 ipv4 0.0.0.0:22 cupsd 1324 1324 root 11 ipv4 127.0.0.1:631 cupsd 1324 1324 root 12 ipv4 0.0.0.0:631 dhclient 15162 15162 root 20 ipv4 0.0.0.0:21976 dhclient 15162 15162 root 6 ipv4 0.0.0.0:68 DOM 52382 24604 root 46 ipv4 192.168.199.193:50549->74.125.239.105:80 DOM 52382 24604 root 47 ipv4 192.168.199.193:44254->74.125.239.142:80 DOM 52382 24604 root 38 ipv4 192.168.199.189:46951->63.245.216.132:443 firefox 52382 28734 root 46 ipv4 192.168.199.193:50549->74.125.239.105:80 firefox 52382 28734 root 47 ipv4 192.168.199.193:44254->74.125.239.142:80 firefox 52382 28734 root 38 ipv4 192.168.199.189:46951->63.245.216.132:443 dhclient 33763 33763 root 20 ipv4 0.0.0.0:46380 dhclient 33763 33763 root 6 ipv4 0.0.0.0:68 sendmail 33786 33786 root 4 ipv4 127.0.0.1:25

Hmm, firefox shouldn’t be run as root… And here are all the files currently open under /etc:

$ sudo sysdig -c lsof "'fd.name contains /etc'"

COMMAND PID TID USER FD TYPE NAME systemd-udevd 359 359 root 11 file /etc/udev/hwdb.bin proftpd 40759 40759 daemon 3 file /etc/group proftpd 40759 40759 daemon 4 file /etc/passwd

ps + filters

I find the ps chisel even more interesting. It’s like ps on steroids, because you can specify conditions on both what the process is and what it’s doing. Let me give you some examples. This lists the processes or threads that act as servers on ports different from 80:

$ sudo sysdig -c ps "'fd.type=ipv4 and fd.is_server=true and fd.sport!=80'" TID PID USER VIRT RES FDLIMIT CMD 539 539 chrony 22.02M 592.00KB 1024 chronyd 891 891 root 80.59M 216.00KB 1024 sshd 896 896 rpc 18.72M 220.00KB 1024 rpcbind 1324 1324 root 201.91M 1.18M 4096 cupsd 15162 15162 root 92.54M 952.00KB 1024 dhclient 33763 33763 root 92.54M 1016.00KB 1024 dhclient 33786 33786 root 92.20M 612.00KB 1024 sendmail 38081 38081 redis 1013.47M 2.38M 4016 redis-server 38082 38081 redis 1013.47M 2.38M 4016 redis-server 38083 38081 redis 1013.47M 2.38M 4016 redis-server 41113 41113 mysql 269.44M 30.75M 1024 mysqld 41122 41113 mysql 269.44M 30.75M 1024 mysqld 41123 41113 mysql 269.44M 30.75M 1024 mysqld 41124 41113 mysql 269.44M 30.75M 1024 mysqld 41125 41113 mysql 269.44M 30.75M 1024 mysqld 41126 41113 mysql 269.44M 30.75M 1024 mysqld 41127 41113 mysql 269.44M 30.75M 1024 mysqld

This lists the processes that have files open in /etc and have network connections:

$ sudo sysdig -c ps "'fd.name contains /etc or fd.type=ipv4'" TID PID USER VIRT RES FDLIMIT CMD 539 539 chrony 22.02M 592.00KB 1024 chronyd

and this is the list of processes that don’t have bash as an ancestor or, in other words, the list of system processes:

$ sudo sysdig -c ps "'not(proc.aname contains bash)'" TID PID USER VIRT RES FDLIMIT CMD 1 1 root 50.31M 3.09M 65536 systemd 359 359 root 41.93M 752.00KB 1024 systemd-udevd 361 361 root 50.21M 1.07M 16384 systemd-journal 472 472 root 49.75M 276.00KB 1024 auditd 483 472 root 49.75M 276.00KB 1024 auditd 484 484 root 78.30M 196.00KB 1024 audispd 486 486 root 23.35M 180.00KB 1024 sedispatch 487 484 root 78.30M 196.00KB 1024 audispd 496 496 root 140.09M 468.00KB 1024 abrtd 498 498 root 137.93M 308.00KB 1024 abrt-watch-log 499 499 root 4.17M 60.00KB 1024 rngd 502 502 root 137.93M 292.00KB 1024 abrt-watch-log 509 509 root 32.14M 572.00KB 16384 systemd-logind 510 510 root 286.46M 1.02M 1024 accounts-daemon ...

Well, you get the idea: the same

language that you use to filter sysdig events can be used to filter the process list.

lsof and ps + time navigation

I’ve shown how to decide what to see, now let’s get into the when. The lsof, ps, and netstat chisels show you the content of sysdig’s process table when they receive the first event from the sysdig capture. This means that, by default, they stop and dump the table right away (at event number 1), very similarly to what the real ps, lsof, and netstat do. However, the first received event is controllable with a capture filter, and that lets us get the result at a precise point in time, which is impossible to do with the original unix command lines. Let me give you an example: suppose I want to figure out if my program is leaking file descriptors. One way to do it is by checking the program’s list of open file descriptors when it exits. This is something lsof would be perfect for, the only problem is: it’s absolutely not trivial to synchronize lsof so I can get its output exactly when my program exits. With sysdig? A simple command line:

$ sudo sysdig -c lsof "'proc.name=myapp'" proc.name=myapp and evt.type=procexit COMMAND PID TID USER FD TYPE NAME myapp 43073 43073 loris 0 file /dev/pts/15 myapp 43073 43073 loris 1 file /dev/pts/15 myapp 43073 43073 loris 2 file /dev/pts/15 myapp 43073 43073 loris 3 file /home/loris/myapp.log myapp 43073 43073 loris 4 file /home/loris/myapp.log myapp 43073 43073 loris 5 file /home/loris/myapp.log myapp 43073 43073 loris 6 file /home/loris/myapp.log myapp 43073 43073 loris 7 file /home/loris/myapp.log myapp 43073 43073 loris 8 file /home/loris/myapp.log myapp 43073 43073 loris 9 file /home/loris/myapp.log myapp 43073 43073 loris 10 file /home/loris/myapp.log myapp 43073 43073 loris 11 file /home/loris/myapp.log myapp 43073 43073 loris 12 file /home/loris/myapp.log myapp 43073 43073 loris 13 file /home/loris/myapp.log myapp 43073 43073 loris 14 file /home/loris/myapp.log myapp 43073 43073 loris 15 file /home/loris/myapp.log myapp 43073 43073 loris 16 file /home/loris/myapp.log myapp 43073 43073 loris 17 file /home/loris/myapp.log ...

Note how this time there are two filters on this command line:

- The first filter is in the quotes and specifies what I want to see – in this case, I want to see the file descriptors for processes called ‘myapp’.

- The second filter determines when I want to see it, and means “wait until a procexit event arrives for a process called myapp.” Procexit is generated when a process ends its life, either in a clean way or because of an error.

Clearly it looks like my program forgot to close the file after writing to its log file. Let’s fix the program and try again:

$ sudo sysdig -c lsof "'proc.name=myapp'" proc.name=myapp and evt.type=procexit COMMAND PID TID USER FD TYPE NAME myapp 43073 43073 loris 0 file /dev/pts/15 myapp 43073 43073 loris 1 file /dev/pts/15 myapp 43073 43073 loris 2 file /dev/pts/15

Much better – this is what I would expect from a properly behaving program: stdin, stdout and stderr.

Final notes

Getting the list of file descriptors when a process exits is a good showcase for the time navigation feature, but there are several other interesting use cases. For example:

- Look at the FD table when a specific I/O error occurs. The evt.failed and evt.res filter fields are your friends here.

- Explore system state around a log event. Refer to the recent blog post on sysdig + logs for filter examples.

- Explore system state at a specific time, by using the evt.datetime filter.

Also, a few things to keep in mind:

- All of the examples in this post will work with trace files as well. As I mentioned, sysdig dumps the content of /proc in each trace file, and then updates the state for each event. The result is that you can run ps or lsof at any arbitrary point in the capture.

- One of the big advantages of the approach used by sysdig is low overhead. Since the FD table is kept in memory and built incrementally, it can be dumped with very low overhead and without generating a burst of accesses to /proc around the observation point.

- This low overhead becomes particularly interesting when you keep in mind that this functionality is consumable through the chisels Lua API. The lsof, ps, and netstat chisels are just trivial wrappers around the sysdig.get_thread_table() chisel API function. A lot more interesting stuff can be built on top of it. Did I hear somebody say top time travel? :-)